38: Sigmund Freud: Civilization and Its Discontents, Part One

We all know Freud by name and countless mainstream Oedipal references, but I feel few of us have actually read his original primary texts. I kept finding myself asking, what is a Freudian slip anyway? I still don’t know actually, that wasn’t in the book I read, but I digress.

Sigmund Freud is the father of psychoanalysis, of course. He was born in 1856 in Czechoslovakia, moved to Vienna, Austria in childhood, and later attended the University of Vienna to study medicine: specifically physiology and neurology.

Influenced and encouraged by French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, “nervous ailments became Freud’s speciality, and in the 1890s, as he told a friend, psychology became his tyrant. During these years he founded the psychoanalytic theory of mind.”(154)

Freud specifically studied hysteria, early family dynamics in shaping the unconscious, psychoanalysis through dreams, and more questions around human neuroses and the psychological origins of modern civilization. “Two principal sources of hope for the future of Freud’s ideas [...] were Socialist Viennese physician Alfred Adler (1870-1937), and the original, self-willed Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung (1875-1961).”(154) Freud died in 1939 by requesting a lethal dose of morphine from his physician after a long fight with cancer.

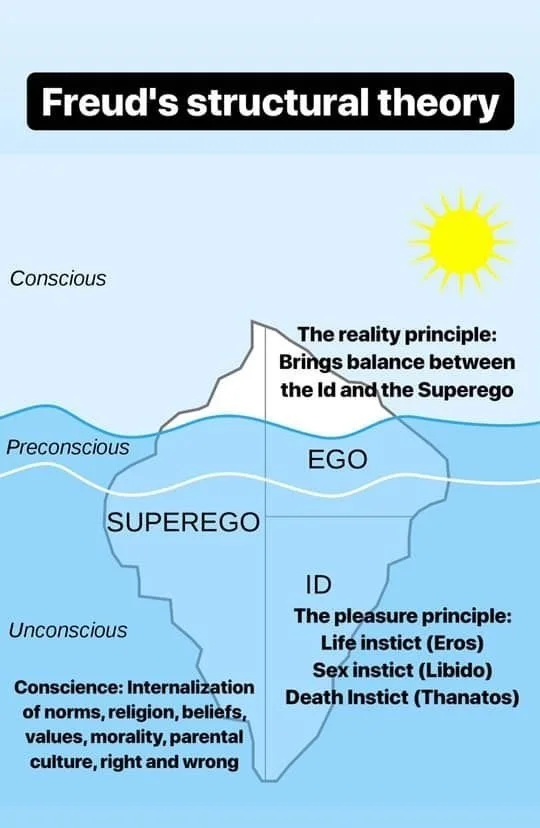

One of his most famous works was Civilization and Its Discontents, published in 1930, and with countless ideas that were well ahead of his time. The main concepts of this major work were that of the death instinct, the pleasure principle, aggression, and primal guilt. It was these four concepts that Freud posited as the origins of much of human “progress”, dysfunctions, neuroses, and conflicts both internal and external.

In part one of this blog series, we will focus on the pleasure principle and aggression because it seems they are intertwined, though without becoming clear opposites in relation.

Freud understood that people: “strive after happiness; they want to become happy and to remain so[...] It aims, on the one hand, at an absence of pain and unpleasure, and, on the other, at the experiencing of strong feelings of pleasure[...]As we see, what decides the purpose of life is simply the programme of the pleasure principle.”(43)

He then goes on to analyze the fact that if or when someone achieves their desires toward pleasurable ends, it is never enough for long. There is a universal recognition that we simply cannot always get what we want because the fun and growth is in the challenge. The Yin and Yang. Sisyphus never makes it to the top of the hill, because… then what? We cannot fathom things beyond linear time (yet) anyway.

“We are so made that we can derive intense enjoyment only from a contrast and very little from a state of things. [footnote: Goethe, indeed, warns us that ‘nothing is harder to bear than a succession of fair days.’”(43)

I am feeling this now myself, as I’m underemployed until March and have a lot of free time, which explains why I’m writing this blog post (it is a necessary brain workout to keep it from becoming mush to feed to the various social media algorithms that fuel the bank accounts of the global elite hehe).

The point being--I am having a “succession of fair days” because of my unfettered free time, and after a while, it's become harder to recognize the beauty of it; something that was once automatic gratitude has become an active practice. This is the contradistinction of Freud’s pleasure principle, that what once brings us pleasure may not do so forever.

This leads into the concept of human aggression, a drive Freud identifies as a source of the “progress” of civilization in a very Darwinian sense. It is the idea that our pleasures must be fought for, that there are few beyond the natural gifts of living that come free.

“Aggressiveness was not created by property[...]If we were to do away with personal rights over material wealth[...]we cannot, it is true, easily foresee what new paths the development of civilization could take; but one thing we can expect, and that is that this indestructible feature of human nature will follow it there.”(11)

Freud makes the distinction that aggression existed before the concept of property and human ownership, before the denotation of the “self” among “others” (i.e. “mine” vs. “yours”) that once, presumably, functioned as one community in the earliest societies.

“The fateful question for the human species seems to me to be whether and to what extent their cultural development will succeed in mastering the disturbance of their communal life by the human instinct of aggression and self-destruction.”(149)

This reminds me of how individual self-preservation requires some element of defensive aggression, alongside the wider scope of the tragedy of the commons and the tyranny of cousins. Let’s define these real quick for those who often forget (like me):

The tragedy of the commons is “a situation where individuals, acting in their own self-interest, overexploit a shared resource, leading to its depletion and ultimately harming everyone who relies on it, because there are no regulations or incentives to manage the resource sustainably; essentially, everyone using a common resource at their own discretion can lead to its destruction for all.” (AI Overview, Google)

The tyranny of cousins is a concept coined by Fukayama in his book titled The Origins of Political Order, “Typically, tribal societies are characterized by segmented groups ruled by what Fukuyama calls “the tyranny of the cousins.” Segmentation allows tribes to mobilize quickly for conquest, but internal squabbles among extended kinship groups hinder their ability to govern the vast territories they’ve conquered.”(source). In this case the “kinship groups” can simply embody those who denounce the supposed human aspect of aggression, and those who don’t.

Freud pointed out how aggression may manifest within civilization regardless of parameters put in place in the interest of human “optimization” in the hopes of egalitarianism, that those who sacrifice their advantages and admonish aggression end up losing in a world of offensive acts. I think of Vonnegut’s character Harrison Bergeron.

“Civilization pays no attention to all this, it merely admonishes us that the harder it is to obey the precept the more meritorious it is to do so. But anyone who follows such a precept in a present-day civilization only puts himself at a disadvantage vis-a-vis the person who disregards it. What a potent obstacle to civilization aggressiveness must be, if the defence against it can cause as much unhappiness as aggressiveness itself!”(146)

In tandem, the pleasure principle and aggression go hand-in-hand in a bid toward achieving something desired, as individuals or as a civil society.

I wonder what Freud would have thought of how these psychoanalytic concepts manifested into future research into the mind.

In the next part of this blog series, we’ll focus on the other two of the four aspects in Civilization and Its Discontents: primal guilt and the death instinct.

Thank you for reading! Please feel free to comment below or start a conversation about a concept or how this can apply in present day society.