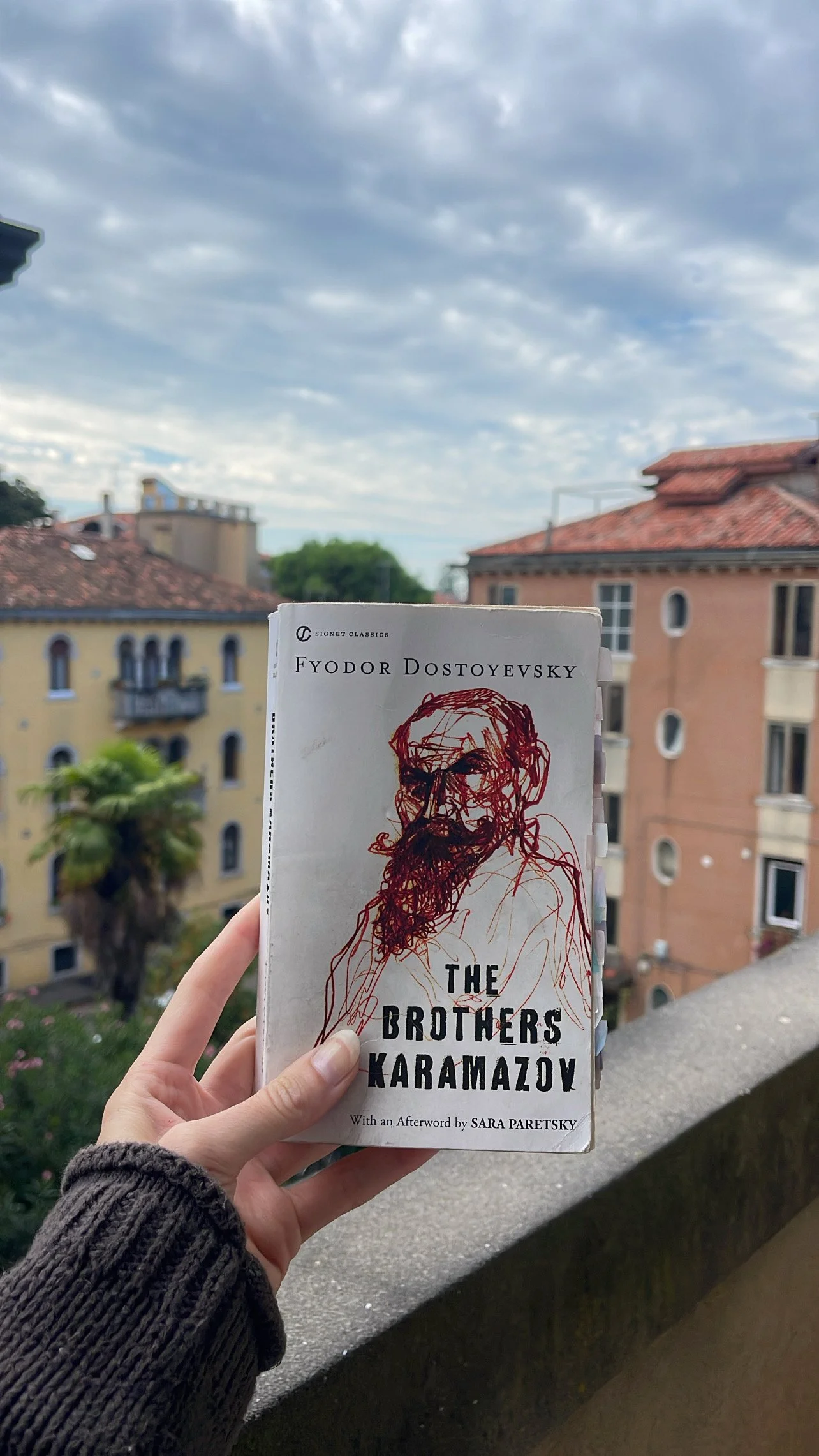

26: Book Review 10: The Brothers Karamazov

*This book review does not contain spoilers*

Dostoevsky has a supernatural gift for capturing the essence of the human condition across time and culture. After reading Crime and Punishment last year, I thought it only natural to read his other revered work, though 897 pages was quite a commitment. Below I share with you a glimpse into the reverent, dramatic, and often philosophical transcendence of his writing, save for the occasional laughs we’ll get to later.

“I have a longing for life, and I go on living in spite of logic. Though I may not believe in the order of the universe, yet I love the sticky little leaves as they open in spring. I love the blue sky.[...]I love some great deeds done by men, though I’ve long ceased perhaps to have faith in them[...]I want to travel in Europe, Alyosha. And yet I know that I am only going to a graveyard, but it’s a most precious graveyard, that’s what it is! Precious are the dead that lie there. Every stone over them speaks of such burning life in the past, of such passionate faith in their work, their truth, their struggle and their science.[...]And I shall not weep from despair, but simply because I shall be happy in my tears. I shall steep my soul in my emotion.”(260)

This was one of many quotes that spoke so directly to me that I literally teared up reading it. It was spoken by Ivan to his brother Alyosha over drinks and in the midst of the type of existential conversation that often transpires with those we are closest to, those we do not fear judgment from.

What a beautiful soliloquy on the lust for life. Queue Lana Del Rey. The reference to Europe as “a most precious graveyard” is one of the most unique yet accurate ways I’ve ever heard it described.

One month ago, I was traveling around Italy with my family before settling into my new home in Venice, and we stopped at the Vatican. When I entered the courtyard of St. Peter’s Square on that bluebird day, I was absolutely astonished at how massive it was, at the hundreds of statues gracing the pillared, vaulted verandas. I stood in the center, slowly spinning, looking up, and was struck dumb by the evident years, centuries of craftsmanship, artistry, care, and dedication that architectural feats such as that require. Dostoevsky sprinkled in his appreciation for human accomplishment, Russian or not, especially for cultures as old.

Dostoevsky wove a wonderful, tangled web of family conflict with The Brothers Karamazov. Though the major conflict ends in a court verdict with no true final resolution (he did not live to write a potential sequel) and a heart wrenching death of universal sympathy, the reader remains a witness to the range of human plight, from the loss of childish innocence to a tangled murder. He ponders the philosophical questions of character, of essentialism versus constructivism: What makes a person good or bad? Are we ever able to decide definitively, and on behalf of others we can barely know as well as ourselves? And are people themselves categorical, or only their actions?

He asks us if we can truly know what we’re each capable of, or if instead we must resign ourselves to the principle of Occam’s razor, taking people's actions at face value and unconditionally labeling them a flattened “other” for a faster, deceptively neat, conclusion.

“As a general rule, people, even the wicked, are much more naive and simple-hearted than we suppose. And we ourselves are, too.”(6)

Dostoevsky asks us to withhold from snap judgment, to acknowledge the shades of nuance in others that we so easily grace upon ourselves. Both Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment and Dimitri in The Brothers Karamazov were perfect examples of people with dodgy records, moments of aberration, lapses in judgment, foolish desperation, and spite. Dimitri even frequently referred to himself as a “scoundrel”.

In both stories, it was only through the grace of others who gave them a chance to explain themselves that any kind of consolation was achieved. Consolation and closure, of course, are not the same as forgiveness, and do not lessen the mistakes we make against each other. Consolation may instead cast a clear, warm light onto that which we’ve done, for better or worse.

“Everywhere these days men have ceased to understand that the true security is to be found in social solidarity rather than in isolated individual effort. But this terrible individualism must inevitably have an end, and all will suddenly understand how unnaturally they are separated from one another.”(347)

With the theme of family and community woven throughout this tome of a novel, it was only through solidarity that the characters were able to put aside another’s wrongs to help, in acknowledging that we are all imperfect and often mistaken ourselves. Sometimes we cannot do it alone, sometimes we cannot help ourselves, sometimes—especially when we may most resent it—we need each other.

This reminded me of a quote from Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, which I gleaned from a book reviewing podcast:

“He had the unfortunate capacity that many men have, especially the Russians, for seeing and believing in the possibility of goodness and truth. Yet seeing the evil and falsehood in life too clearly to be capable of taking any serious part in it. Every aspect of human activity he saw was bound up with evil and deception. Whatever he tried to be, whatever he decided to do, he found himself repelled by evil and falsehood with every avenue of activity blocked off. And meanwhile, he had to live on and find things to do, he was too horrible to be ground down by life’s insoluble problems, so he latched onto any old distraction that came along just to get them out of his mind. He tried all kinds of society, drank a lot, bought pictures, built things, and most of all he read.” (Tolstoy, 591)

Both Tolstoy and Dostoevsky touch on this sense of goodwill apparent in Russian culture. That though life can lead us into metaphorical traps, impossible circumstances, or utter despair as it happened to Dimitri, we have to retain a semblance of light-hearted absurdism, of hope and the ability to laugh.

“‘There would have been no civilization if they hadn’t invented God’, said Ivan. ‘Wouldn’t there have been? Without God?’ ‘No. And there would have been no brandy either.’”(152)

Dostoevsky has a cheeky way of sneaking in a laugh, usually in the midst of a heavy dialogue or moment of seriousness. This sprinkling of frivolity at just the right time is an art in itself. It’s something I love about his writing.

Altogether, The Brothers Karamazov was a long one, and while I felt it dragged in the middle and began to get bogged down by the inner workings of a court system (accurately, at least), it revved back up toward an ending of human sympathy, hope, and a sense of introspective benevolence.

I would recommend this read to people who enjoyed Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, The Stranger by Albert Camus, or The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck.

Thank you so much for reading! Feel free to subscribe from the dropdown menu at the top. I send out weekly emails with blog updates, art shop drops, and exclusive discounts.

Also, feel free to leave a comment below, I would LOVE to engage people on this book or others like it.

- Gabby