18: Simulation and AI

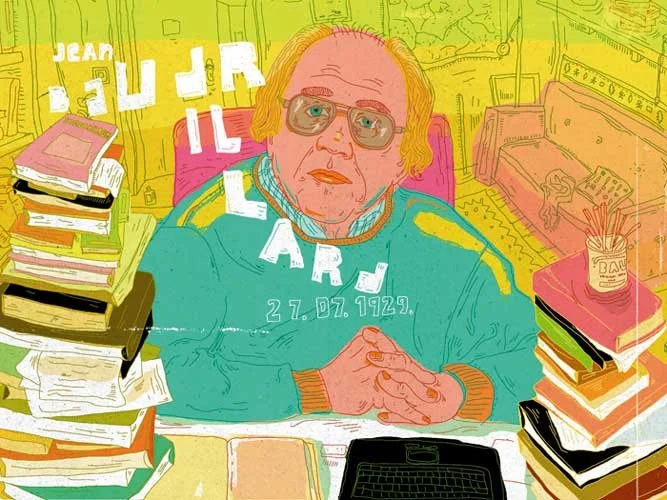

Blog 17, the first of three posts on Simulation, discussed the concept of the “inflation of information and the deflation of meaning”(79), initially explored by Jean Baudrillard in 1981. During that wild ride, we explored the idea that there may no longer be such a practice as “conscious consumption” in the algorithmically supercharged world of social media, that social media creates simulated sociality--substituting the signs of the real for the real, threatening the critical judgements between “true” and “false”--and promoting the most reactive content. And so, we arrive at the deflation of meaning.

This week we’re surfing into how social media and AI(Artificial Intelligence) fit into the previously pondered ideas of postmodern electronic media, simulacra, and the question of hypersimilitude.

Baudrillard argued that there are hypothetically three orders of simulacra: simulacra that are natural, simulacra that are productive, and finally, simulacra of simulation (121). I would argue we have entered the throes of the third order in which “simulacra of simulation are founded on information, the model, the cybernetic game--total operationality, hyperreality, aim of total control.”

The third order corresponds to the “operational (the cybernetic, aleatory, uncertain status of ‘metatechnique’)”(121). I believe this has begun happening in the world of social media where people have gained access to ways to make financial gain through affiliate marketing for instance, where people model themselves after edited photos of surgically-altered bodies, where algorithms create a sort of stream-like system of connections toward ultimately deeper and deeper ravines of increasingly disparate ideas and worldviews. We have begun to reference ourselves in this third order. To pretend in a photo, edit it, post it, go viral, and then have other people absorb it as face value and try to imitate it themselves is a perfect demonstration of simulation on a small and deceptively inconsequential level. We have “content-ified” reality. Notice, too, how Baudrillard mentions the term ‘metatechnique’, a type of self-referential watering down of experience through simulation.

It is no coincidence that Facebook, arguably the first widely adopted social media platform that revolutionized online global human connection, changed their company name to Meta in late 2021. They are pivoting toward the ever-growing world of simulation, into the “Metaverse”, where people will one day, through VR (virtual reality), interact in simulated social circumstances as if they are standing in front of one another, save the other four senses.

Baudrillard’s third order of simulacra reminded me of how social media algorithms are a form of AI working in the background of all our online experiences. In Max Fisher’s book, “The Chaos Machine”, published in 2022, it’s explained how social media algorithms end up inadvertently promoting morally challenging or conflict-oriented content because it produces the most views by virtue of our inherent genetic desire to adhere to the in-group and denounce aggression or problems with anger. Anger and outrage travel more than any other emotional reaction on social media, which is why issues so quickly devolve to cancel culture, conspiracies, and paranoid misinformation. Apparently, “moral emotional words” travel 20% farther on social media, especially to those on the same “side”, creating groupthink, positive reinforcement, and disparaging social outgroups. This “us” vs. “them” mentality stirs our collective hive mind into believing there is, in actuality, intense polarization in the everyday world around us, when really, it is not as bad as it appears online.

How does this tie into Baudrillard’s theoretical conjectures? Well, AI algorithms are instilling in their viewers the textbook definition of hyperreality: the inability of consciousness to distinguish reality from a simulation of reality. Is everyone (but you) suddenly super beautiful or is that just the algorithm simulating a constant feed of screen-time-extending fascination?

“Implosion of meaning in the media. Implosion of the social in the masses. Infinite growth of the masses as a function of the acceleration of the system. Energetic impasse. Point of inertia. A destiny of inertia for a saturated world. The phenomena of inertia are accelerating (if one can say that). The arrested forms proliferate, and growth is immobilized in excrescence”(Baudrillard 161). Excrescence: an outgrowth, an abnormality.

Beyond algorithms, there is also the newer phenomena of AI-generated writing, imagery, and artwork by way of prompts and the ever-increasing web of associations. In the “Sounds of Sand” podcast episode #64: AI & the Global Brain, Peter Russell (who coined the term “Global Brain” in 1982) explains that AI is “not a sort of linear system, it’s recursive so your question has actually changed the parameters by which it’ll give you the next answer. From what my limited understanding of it is, it’s so much more complex than a predictable answer coming from a database, it’s complex with sort of like vectors and weights and the way it connects words in this 3 dimensional way[...]I prefer the term simulated intelligence, it isn’t artificial because it’s simulating intelligence.”

What struck me about Russell’s description of AI systems like ChatGPT, was his distinction between artificial and simulated. He argues that it is simulated, “AI is verbal intelligence, simulating our thinking mind. There’s no sensory information.” The Oxford Dictionary defines artificial as “made or produced by human beings rather than occurring naturally, especially as a copy of something natural”, and simulated as “manufactured in imitation of some other material.”

When AI is imitating human-produced art, ways of speaking, etc., it has moved beyond artificial and into simulation.

Forgive the lengthiness of this quote, but I think this perfectly articulates my mode of thinking when it comes to AI-generated art, as one of many artists feeling encroached upon. “It is necessary to revisit what Walter Benjamin said of the work of art in the age of its mechanical reproducibility. What is lost in the work that is serially reproduced, is its aura, its singular quality of the here and now, its aesthetic form (it had already lost its ritual form, in its aesthetic quality), and, according to Benjamin, it takes on, in its ineluctable destiny of reproduction, a political form. What is lost is the original, which only a history itself nostalgic and retrospective can reconstitute as ‘authentic.’ The most advanced, the most modern form of this development, which Benjamin described in cinema, photography, and contemporary mass media, is one in which the original no longer even exists, since things are conceived from the beginning as a function of their unlimited reproduction”(Baudrillard 99).

Art is “content-ified”.

Much like Baudrillard, Russell ultimately also submits to the idea that “With the advent of artificially created media, likenesses will be synthesized to the point where you can’t tell if it’s fake anymore. And so we will basically get to a point where we no longer accept anything that’s digital as potentially coming from the real world.” Think of Deepfakes, Facetune, voice synthesization, artificially generated video of politicians addressing a nation. Baudrillard touches on this idea, noting that “Parody renders submission and transgression equivalent, and that is the most serious crime, because it cancels out the difference upon which the law is based”(21).

When society can no longer tell or trust what is real or fake, how will they vote? How will they transgress? How can they rebel without a true sense of reality as it is? How can they know anything?

In the “Sounds of Sand” podcast episode #71: Beyond Algorithms, Edward Frenkel posits, “Alan Turing said there is Will. There is such a thing as Will. He’s on record saying that, the father of modern computing, that computers, machines are only capable of doing some clerical work without true understanding. The word intelligence comes from Latin intelligere, which means understanding. How can you call this computer program intelligent if they do not have any true understanding?”

Frenkel creates hope in the face of an impending theoretical singularity, noting that human beings have always created tools to further our abilities, creativity, and ultimate potential. He begs the question, what can we do that AI could never do? What can we create that cannot be recreated, cannot be simulated, manufactured, or posed as original? If AI reaches “singularity”, will it ever achieve agency, or will it only simulate it?

The existential framing of human will puts me in mind of Anthony Borges’ famous novel “A Clockwork Orange”, when the main character Alex is told in his imprisonment, ‘Goodness comes from within, 6655321. Goodness is something chosen. When a man cannot choose he ceases to be a man’ (93).

Even Baudrillard refers to Borges as far back as 1981, “This mutating and comutating world of simulation and death[...]Is it good or bad? We will never know. It is simply fascinating, though this fascination does not imply a value judgment[..]Nowhere does this moral gaze surface--the critical judgment that is still part of the functionality of the old world[...]few books, few films reach this resolution of all finality or critical negativity, this dull splendor of banality or of violence. Nashville, A Clockwork Orange.”(119).

The question of hypersimilitude, then, enters into the realm of philosophical inquiry. As long as man can choose to either regulate an online world into a trustworthy space of human connection and creativity, or disassociate from it altogether without becoming socially inert, there is hope yet.

In the next and final post of this three part series, I will be exploring if and how Baudrillard’s “Simulacra and Simulation” stands the test of time compared to more modern explorations of AI and predictive arguments for or against the possibility of achieving “Singularity”.

Thanks for reading!

Gabby